In 1953, the year I was born, the choreographer Merce Cunningham formed his dance company at Black Mountain College, North Carolina. The composerJohn Cage would be the music director. The college, at which the arts were considered crucial to learning, and which encouraged collaboration and experimentation in a communal atmosphere of shared tasks such as farming and cooking, was a natural crucible for this kind of partnership. Cunningham and Cage collaborated continuously for the next forty years, until Cage's death in 1992, making work which was profoundly radical and enormously influential.

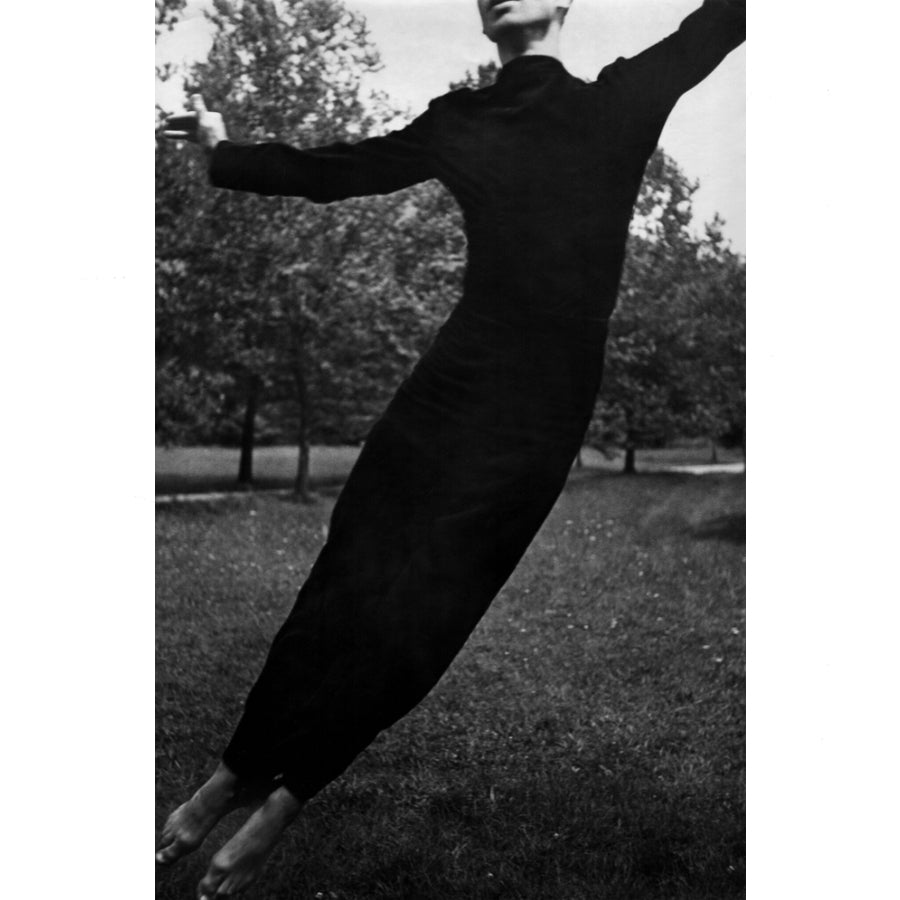

For Cunningham, dance was about moving in spaceand time'. In his work, the movement has no inherent meaning. There are no plots, no characters, no messages, no symbols. It's as if the dancers are scientists, engaged in an exploration of what the body can do. The audience is invited to make whatever sense of the work they choose.

Music, usually by Cage, and sets and costumes by Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol amongst others, were added after the choreography was made, any connections between them spontaneous, accidental. Cunningham felt that movement should be dictated by its own rhythms, not musical rhythms. It is difficult to overestimate how revolutionary this was. In the dance world of the time, the music came first; the movement was invariably inspired by the contours and emotion of the music.

For Cage, music was not about emotion; it was simply about the organisation of sound. And that sound was the entire field of sound', notes played on a piano, yes, but also electronic sounds, the sound of birds, of rain, of radio static, of a truck at fifty miles an hour. Whatis the purpose of writing music?' he wrote. One is, of course, not dealing with purposes but with sounds. Or the answer must take the form of paradox: a purposeful purposelessness or a purposeless play. This play, however, is an affirmation of life... a way of waking up to the very life we're living.'

You can see this philosophy brought to glorious life in a YouTube clip in which Cage appears on the game show I've Got A Secret. He performs a piece titled Water Walk, using a bath, a vase of flowers, a watering can, a pressure cooker, a piano, and several radios. The radios are silent, due to an industrial dispute about which union should turn them on, but Cage finds a use for them. Theseare nice people,' says the host, indicating the audience. He is clearly having a hard time deciding what tone to take. Some of them are gonna laugh. Is that alright?' Of course,' says Cage, deadpan throughout. I consider laughter preferable to tears.' The piece itself is like a strange kind of cookery demonstration. The radios end up on the floor. The audience, bewildered but amused, does laugh.

Cunningham and Cage used chance to generate choreography and music, marking the imperfections on a piece of paper to decide the path of a dancer across the stage, for example, or using the I Ching to decide on the order of a series of sounds. Partly this was to tap into the mysterious operations of the universe, partly to bypass expressiveness (I have nothing to say,' said Cage, andI am saying it'), partly to ward off habit - to generate movement and music that they might not have thought of themselves.

Like Cage, I have spent a lot of my life making music for dance. I have always admired the beautiful simplicityof their collaborative method. My own collaborations with choreographers have been more complex, more varied, more uncertain. I have tried a thousand ways of combining music and movement. Nowadays I seldom write the music first. For most choreographers, as for Cunningham, their primary responsibility is to the dancers. The movement is dictated by its own rhythms. I watch and listen (there is often spoken dialogue), go away, write something, bring it back into the rehearsal room, try it out, adjust it, go away, refine it, bring it back, try it out, finesse it....decide it doesn't work,write something else, bring it in...... Laborious! If only I had the sensibility and the courage to follow Cage and Cunningham's radical lead.

Words byOrlando Gough. As well as being a regular contributor to TOAST Magazine, Orlando is a British composer and has written for ballet, contemporary dance, opera and theatre.

Extracts from Concert for Piano and Orchestra' by John Cage (EP6705) Copyright by Henmar Press, Inc., New York for all countries of the world. Reproduced by kind permission of Peters Edition Limited, London.

Add a comment