There is a 4,000-year-old Neolithic standing stone row on Meg Rodger’s croft on the island of Berneray in the Outer Hebrides. Over time, Meg has studied the monument and realised that it lines up with the equinox – the point at which, twice a year, the sun is exactly above the equator, resulting in an equal length of day and night. “It got me thinking about deep time and temporality within this landscape,” she says.

The landscape of Berneray is characterised by the machair – the low-lying, fertile grassland that blankets the west of the island. As a shepherdess with a flock of 130 native Hebridean sheep to tend, Meg is constantly immersed in this landscape: its seasonal rhythms inform her daily life. “When the Arctic Tern comes back in mid-April, I know that spring is here, which for me, means lambing,” she explains. “And then the flowers return to the machair – orchards and primroses early on, followed by corn marigolds and poppies in July and August, when I’ll be shearing. There is a very definite cycle.”

The backdrop to this seasonal cycle is the weather on Berneray. At 57 degrees north and only 9 degrees below the Arctic circle, life on the island is defined by sunlight, darkness and, “more than anything,” the wind.

Like many island inhabitants, Meg has multiple jobs. As well as managing her flock, she is an environmental artist who, for several years, has collaborated with the wind to produce a series of minimal wind drawings. “I had one of those moments when I realised that actually, it was the wind I had to work with because it was the one thing that was holding me back,” she recalls.

Meg studied art as a mature student, graduating from the University of Highlands and Islands in 2016. It was a distance learning course which, at times, “felt a little too distant,” she recalls. With limited access to technicians and studios on campus, she became more inventive. “In island life, you have to fix everything yourself,” says Meg, “so you end up with a shed full of bits and bobs. So I would just go out to the shed and start making things, and I think, in retrospect, those creative experiments have made my work a wee bit more unique.”

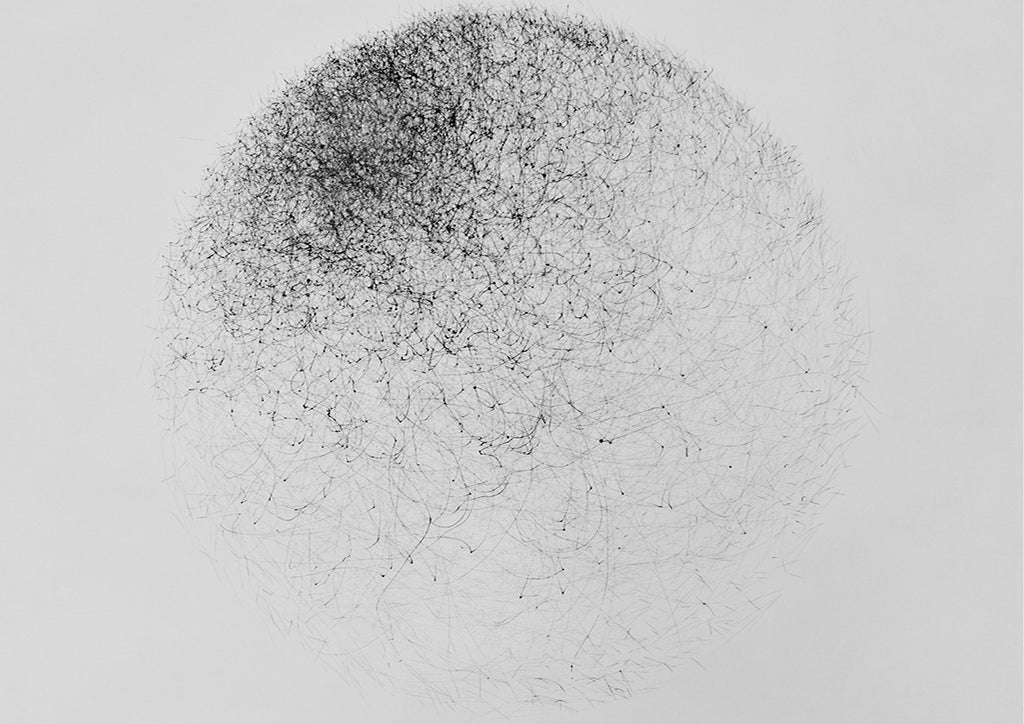

Meg uses two forms of apparatus to create her drawings: an aluminium-framed tripod and a yellow, weighted storm barrel that washed ashore one day. Her large-scale wind drawings are produced on the tripod, which is tethered to the ground and aligned with the four cardinal points: North, South, East and West. A permanent marker hangs from a piece of string in the centre of the tripod. When the wind blows, a mark is made on a sheet of paper affixed to a plywood board. The apparatus is kept close by on the croft in case of sudden showers and monitored for around six hours. The marks that are made become a very genuine record of the wind that day.

The storm barrel, by comparison, is sealed, tethered to the ground and left to record the wind over a 24-hour period. A rod protruding from the lid of the barrel catches each gust and transfers a mark from pen to paper. “I’m never really sure what is going to be under that lid when it’s lifted,” explains Meg. “By no means does it work every time.” Sometimes, the results are “mildly disappointing,” other times – when the full anger of a storm has been recorded in repetitive lines – the results are mesmerising.

The mark-making varies from the fragile to the ferocious. “I can now look at the drawings and tell you what sort of wind it has been on that day,” says Meg. Ink spots indicate rest points where the wind has momentarily died down, whereas the black, solid shapes that emerge after a gale-force storm becomes almost three-dimensional. “I did, at one point, briefly experiment with trying to emulate the marks and you simply can’t draw them by hand,” Meg says.

The black marks describe a loose circle from which a tension emerges that Meg correlates to the environment on Berneray. “I think the harsh beauty that surrounds me comes across in my work and gives it that edge,” she suggests. “Other than a few weeks in the summer, there isn’t really a comfort zone living here. You kind of drop your guard at your peril, especially at sea.”

Each drawing is given the title of the Shipping Forecast from that day. For Meg –whose husband is a marine scientist and lobster fisherman – the Shipping Forecast is a reliable and dependable life-line as well as a rhythmic reminder of her father, who would recite it to his children each day. “Quite often, we get storms that go on for days,” says Meg. “Eventually, the power lines give way and the electricity goes off, so we switch on the radio and listen to the Shipping Forecast in the dark. It’s only telling you what you already know, but it is just so reassuring to know that somebody is still out there.”

Alongside her wind drawings, Meg has begun to create a “Solargraph Sketchbook.” Her solargraphs are made by installing a small pin-hole camera outside in the landscape for several months. As time passes, the changing arc of the sun is etched onto photographic paper, resulting in an iridescent white rainbow of light. “I started to record this sunlight, in a sense, trapping it in these little tin cans,” Meg explains. “Once revealed, they make visible that which we no longer take time to observe, but which our ancestors studied enough to build monuments in honour of.” As with her wind drawings, the solargraphs are rooted in rhythms that are vast, infinite and constant. “No matter what us human beings get up to,” she reflects “these are all systems that are far greater than ourselves.”

In recent months, the writer Nan Shepherd has re-emerged as a guiding influence for Meg: “She’s on my shoulder a lot of the time.” Her book, The Living Mountain – about a woman’s relationship with her environment and landscape – is a text Meg has returned to many times. “It’s about a peaceful, respectful way of being in the landscape,” she explains. “It’s about slowing down, breathing the air and watching bugs in the heather or studying moss on a stone … It’s the small things, you know. I think we can take an awful lot from that.”

Interview by Nell Card.

Photographs by Cara Forbes.

For more of Meg Rodger's captivating work, see her website.

Add a comment