Corinne Julius visits the studio of Mir on the island of Mallorca.

Perched on a terraced hillside, overlooking the Mediterranean, is the studio of the painter Joan Miro, designed in 1953 by architect Josep Lluis Sert. Sparkling white and modernist in feel, it has a roof of barrel vaulted forms, echoing the architectural traditions of Mallorca.

Inside, the two storey space is light and airy a strictly organised place of work. Canvasses are stacked around the perimeter, some face to the wall, but most with the paintings facing outwards. The studio's long north facing wall has large strips of windows, whilst the opposite wall has two big rectangular windows, which are screened, filtering the view over the Mediterranean. The floor is tiled in large rectangular blocks that sing of the earth and the end wall is composed of blocks of stone. The studio feels rooted in the land, but creates an airy, yet womb-like space.

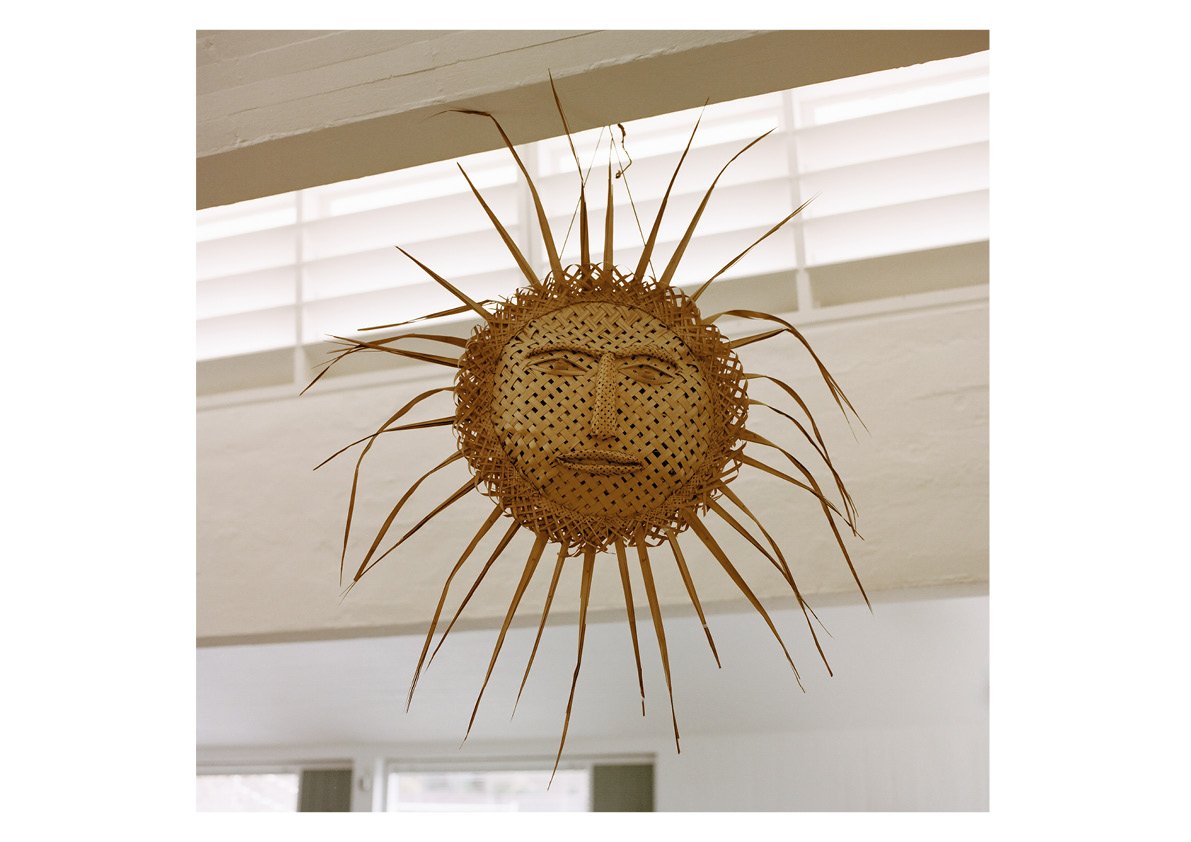

The surfaces of trestle tables are covered in pots containing a range of big, thick brushes, as well as paint. Images and cuttings are pinned to some of the walls, but everything has its order, its place. A gallery overlooks the space and here are collections of driftwood, stones and examples of folk art. It is a very special environment, the spiritual and physical birthplace of the painter's art.

Miro's art is not quiet or restrained. It is bold, powerful and expressive. He uses mainly primary colours, with bursts of green and sweeps of strong black lines. The work looks as if it is spontaneous, but says Patricia Juncosa Vecchierini, curator at the Fondacion Miro, Before starting work, Miro would prepare himself mentally, through poetry, music, a Zen-like meditation. Then he would paint a line in an instant, but behind that lay preparation, preparation, preparation. To do a line in one brushstroke, your head, mind, spirit and hand, have to be ready. He might leave the work to consider, sometimes for years. There was always a tension between the thinking and the doing.

Miro's forms are abstract biomorphic shapes, but certain figures reappear; fecund female shapes, birds, stars and ladders. The woman is Mother Nature, giver of life, the bird symbolises Miro's feet on the earth and his head in the stars. The ladder represents jumping from the earth to the stars. The paintings look like the; work of an impetuous, forceful man, yet Miro himself was quiet, shy and almost reclusive, the antithesis of his compatriots Picasso and Dali. Indeed Picasso used to complain that Miro was boring, appearing as he always did with the same woman, his wife Pilar.

Joan Miro, although born in Barcelona, had strong roots in Mallorca, the home of his maternal grandparents, with whom he spent a lot of time. Pilar, (a remote cousin) was Mallorcan. Miro's father did not want his son to become an artist, so Miro trained and practised as a lawyer, before taking up painting and moving to Paris. Too shy to introduce himself to Picasso when they first met, Miro mixed; in Surrealist circles, though he refused to be defined as one. He was however an avid reader of Surrealist poetry. Andre Breton called him the most Surrealist of us all.

Based in Barcelona between 1931-6, he worked alongside friends including Sert, with whom he collaborated on the Spanish Pavilion at the Paris Expo in 1937, (where Picasso's Guernica was first shown.) The rise of Franco led Sert to flee to the USA, whilst Miro retreated to Mallorca to blend into the background, just the husband of Pilar.' Post-war Miro was desperate to build a studio designed by Sert, however because of Sert's opposition to Franco, he was unable to come back from Harvard Graduate school, where he was teaching, so the pair collaborated by mail.

Miro's brief was eminently practical; the studio had to be designed to take account of Mallorca's climate, the work and storage areas had to be able to cater for his very large canvasses and be clearly separated so that Miro could keep his distance from any canvases that he wished to leave to rest.' It also had to be able to accommodate his collections; especially his folk art pieces such as Mallorcan handmade, decorated, ceramic whistles.

When he first entered the completed studio, Miro was shocked. It was such a large space, says Juncosa Vecchierini. He suffered artist's block. He needed to fill it with objects and drawings. It took him a few years before Sert's building became his studio. Ultimately he found it the perfect place for him to retire and work. He wanted and was, rooted to his terroir. He could isolate himself and capture, the light and colour and his feelings and perceptions of the landscape.

Mir's wife Pilar would clean up quietly in his absence, replacing every item exactly where she had found it, but no one could disturb his working. His routine was to wake early, come down the stairs from his house just above and sit to prepare himself. In Mallorca he didn't use his dreams in a Surrealist way, but said, When I'm sleeping I'm working and when I'm awake I'm dreaming. He worked with canvasses on easels, but also on the floor. He might use the balcony to look down on his paintings or would rest them,' often for years before completing them, using the space just as he had described in his brief to Sert.

Miro was stimulated by anonymous folk art, of which he amassed a large collection, displayed in his studio on cabinets, designed in collaboration with Sert and made by the family furniture business. But the land was particularly important to Miro; he took regular walks around specific paths in the Mallorcan mountains and on the beach. He even had a special pocket made in his suits to hold a carob bean to remind him of his connection to the land. He used the natural objects that he found in these peregrinations, in his sculpture, but also as forms in his paintings. Mallorca was so important to Miro. The imprint of this landscape lives within him and affects his work, says Juncosa Vecchierini. He had nothing to prove to anyone, except himself. He was constantly challenging himself. In the end, in his landscapes, he found that the maximum freedom is a simple line.'

After his death the studio was bequeathed to the City of Palma, who have just entirely refurbished it though refurbishment seems too small a word, for the combination of archaeological dig, academic investigation, engineering and architectural expertise behind it. The work allowed the Fondacion to restore the studio to how it would have been when Miro was in residence. We did everything again, says Juncosa Vecchierini. We mapped everything, looked at old inventories, old films, talked to family members. Miro had a way to move round his studio, we have reinstated that rhythm.

Words by Corinne Julius. Photography by Kendal Noctor. Thank you to the Fundacio Pilar i Miro for granting us permission to photograph Joan Miro's studio.

Add a comment