Now Assistant Curator of International Art at Tate Modern, Sarah Allen began her career at some of the world’s most prestigious galleries and museums including The Guggenheim in New York, as well as The Photographers’ Gallery, London. We meet her in Tate’s Blavatnik Building to discuss her work on a retrospective of pieces by Sophie Taeuber-Arp in collaboration with MoMA and the Kunstmuseum Basel.

Considered one of the foremost abstract artists and designers of the 1920s and ’30s, Taeuber-Arp was “in the centre of this milieu of the most experimental avant-garde artists in Zurich at the time,” Sarah remarks. Truly multidisciplinary, she produced a spectacular array of pieces: paintings; sculptures; marionettes; reliefs; drawings; embroideries; soft furnishings; beaded accessories; stained glass; as well as furniture and axonometric drawings for interiors, such as for the Café de l'Aubette, Strasbourg. The exhibition has examples of each—“really the ambition of the show is to show the full breadth of Taeuber-Arp's practice.”

Sarah considers herself to have had a classic academic training, having read Art History at Trinity College, Dublin. Following her studies, she developed a strong interest in photography; at Tate, she has worked on shows focused on that medium, such as the mid-career survey of Zanele Muholi.

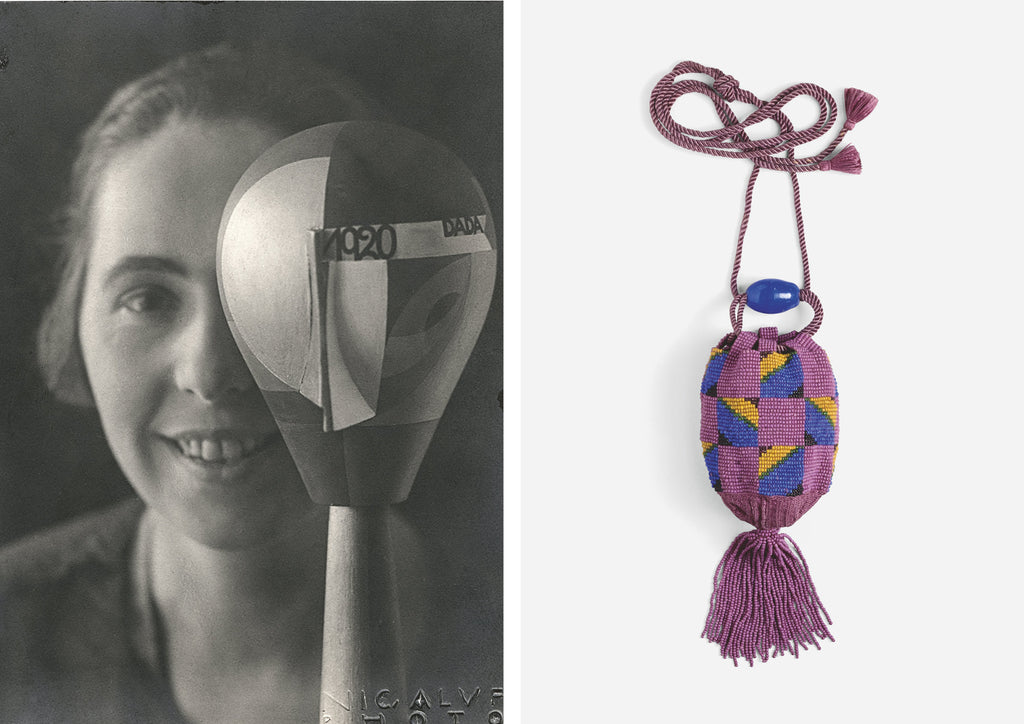

There are few photographs in the Taeuber-Arp retrospective, yet those included are striking and shine a light on the artist’s practice. There are two prints representing the artist’s Dada moment, where she is performing with her Dada Heads, a series of turned-wood sculptures she referred to as portraits. In the photographs, she stands behind them, her face obscured by her creations. Sarah considers them to be some of the “most iconic” images of the Dada movement. “She's presenting herself as a Dada artist. She's got an androgynous look: she can't be seen as a man or a woman. She's just positioning herself as an artist and that's the most important thing.” Also included in the exhibition is a selection of tiny photographs Taeuber-Arp took when she travelled with friends and family. “They’re quick snaps, so they wouldn't really be considered her artistic practice as such,” Sarah says. But they show the artist’s “interest in architecture, the built environment,” and can be used to read her work anew.

A key form of expression for the artist was dance. Sarah, along with the other curators and institutions, considered how that could be represented during the curation process, which she describes as “a beautiful and fruitful dialogue over many years.” That led to the inclusion of what Sarah calls “a very important photograph” of Taeuber-Arp dancing at the opening of Galerie Dada, Zurich. “There are only very few photographs that document what happened at those Dadaist parties, so that's really special,” she enthuses. Sarah also sees Taeuber-Arp’s affinity for dance expressed through the set of marionettes included in the exhibition, which were created for a Dada performance of King Stag, a tragicomedy by Carlo Gozzi, in Zurich, 1918. They're just so stunning. They're the originals and they don't travel often, so it's a really unique opportunity to be able to show them.” The artist was trained in the Laban School of Dance, which was highly experimental—its founder, Rudolf von Laban, focused on abstract understandings of movement, with individual actions visualised through geometric ‘trace forms’. “She loved to dance all her life,” Sarah says. “Those jerky body movements that were often associated with her dance, I feel comes across in the marionettes.”

Taeuber-Arp attempted to “break down the hierarchy” between applied and fine art with her output, Sarah asserts. She often produced the same compositions in different mediums. “She really was an artist who was constantly thinking across many mediums and also reusing ideas, making studies that would then later become a tapestry, for example.” At the time, these textile pieces were exhibited in the context of trade exhibitions, “while textile works by her husband, Hans Arp, were often wall-mounted and seen as fine art and given a specific title,” Sarah explains. “Because she crossed so many different boundaries in so many different disciplines, it was often hard to place her. For a long time, her work has been considered within the realm of applied art. That’s perhaps one of the reasons that has contributed to a lesser spotlight being shone on her throughout art history. That's something we're really hoping to address through the show.”

Interview by Alice Simkins.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp is at Tate Modern until 17 October 2021.

Image 1: Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Tate Modern, 2021. © Tate (Seraphina Neville).

Image 2: Ernst Linck. Sophie Taeuber and Jean (Hans) Arp with her marionettes for King Stag, Zurich, 1918. Gelatin silver print 12.3 Å~ 16. Kunsthaus Zürich Library.

Image 3: Nicolai Aluf. Sophie Taeuber with her Dada head, 1920. Gelatin silver print on card. 12.9 x 9.8. Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin.

Image 4: Geometric forms (beaded bag), 1917. Glass beads, metal beads, thread, cord, and fabric. Height 20.5cm, diameter 7cm. Museum für Gestaltung Zürcher, Hochschule der Künste, Zurich, Decorative Arts Collection.

Image 5: Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Tate Modern, 2021. © Tate (Seraphina Neville).

Image 6: Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Stag (marionette for King Stag), 1918. Oil paint on wood; brass sheet; metallic paint on metallic paper; metal hardware. 50 x 17.8 x 18. Museum für Gestaltung, Zürcher Hochschule der Künste, Zurich. Decorative Arts Collection.

Image 7: Oval Composition with Abstract Motifs (rug), 1922. Wool and cotton.

145cm x 120cm. Arp Museum Bahnhof Rolandseck. Photograph by Mick Vincenz.

Add a comment